Photojournalism

Published News and Feature Stories by Susan Markisz

for The Digital Journalist and Behind the Viewfinder

A Herculean Effort

By Susan Markisz

Photos © Susan B. Markisz for The Montreal Gazette

It took less than two minutes to see that Robyn Brooks is no ordinary 7 year old. Sure, her fire engine red painted fingernails, her constant companion, a stuffed animal named Patch, and a room filled with children's books with fairy tale endings, convey a deceptive sense of normalcy for Robyn, her parents and her 9 year old sister Elise, who moved to the United States from their small town in the UK last year. I only spent a few hours with them, but it was clear that Robyn's mom and dad, Karen and Garry, and her sister Elise, have the weight of the world on their shoulders.

For four of her seven years, Robyn has been battling metastatic neuroblastoma, a rare cancer of the sympathetic nervous system. For over a year, she has been undergoing painful monoclonal antibody treatments called 3F8 that sound more like a photographic term than a cancer-fighting drug.

Robyn, I had been told, is a spunky kid. Her dad Garry indicated that the best time to come would be sometime around 7 or 7:30 in the evening, well after the narcotics Robyn takes, would have worn off. Robyn's best time of day is at night, he told me. We could not get permission, for patient privacy reasons, to shoot at Memorial Sloan Kettering during Robyn's treatments but it was a lovely June evening...still sunny, and breezy - with plenty of time for a walk in the park.

Ronald McDonald House has become the Brookses home away from home for the last year and a half. The room that the Brooks family occupies is about the size of a guest-room in the local Holiday Inn, with two double beds, a mini-refrigerator, microwave...all the comforts of home in miniature, you could say. What it lacks in space, is made up for, by plenty of companionship - a difficult tradeoff that enables them to be surrounded by people who know what they are going through, with a situation that is all too frequently heartwrenching...watching someone else's child relapse, or...their own worst nightmare, die.

"We're pretty lucky, actually," Garry told me at one point. "I mean, from what I've seen here..." he said, as his voice trailed off.

As I entered the darkened room, my pupils dilated. Blankets covered the windows to keep out the daylight so Robyn could finish sleeping off the narcotics that she has to take to stave off the effects of the painful treatments. I could hardly make out her tiny figure, bundled up as she was in a corner of the bed, her huge eyes peeking out from behind the blankets, her fingers clutching its satin binding.

Robyn was having a tough day. Still in a lot of pain, the last thing she wanted to do was to take a walk. What she did want to do, however, was to join her older sister Elise, who was playing bingo in the family room at RMDH. But it took every ounce of energy for Robyn to muster the strength to get going, and by the time we took the elevator down the few flights an hour later, bingo was over and Robyn was crushed. Returning to the room, Robyn's mom and dad read some of her favorite books. Her dad would tell her a joke or make funny faces, and Robyn's pale face would erupt in an engaging smile. Then, solemnly, stoically, he would share a detail or two about her illness. Although Robyn was eligible for the 3F8 clinical antibody trial, her family was ineligible for funding, because they are not American citizens, and they have racked up nearly a million dollars in debt. They have set up a website - The Robyn Brooks Appeal - to help raise money to help pay for their daughter's treatments.

It shouldn't have amazed me but they are relentlessly optimistic and hopeful.

Robyn had already had more than 100 blood transfusions in her short life, and she was soon facing another one. "She's pale," her dad said matter-of-factly, "she's going to need another transfusion soon," a little bit of stoicism in his voice masking concern..

Robyn's mom Karen was exhausted. I so wanted to say or do something to help, but there was nothing to say. My own cancer experience, 15 years ago, was fraught with its own difficulties, and fears. I know the exhaustion; I know the fear; I remember the stoicism. But it wasn't like this. It wasn't my child.

There was one other thing that I saw, though, out of the corner of my eye, that hit me like I had been kicked in the gut. It was Elise. Cancer is a family affair. It does terrible things to a family. There was Elise, her own childhood forever altered. If one were religious, or a philosopher, one could say she might grow up to be more sensitive, or maybe she will be motivated to become a doctor, and find a cure for the terrible cancer that afflicts her little sister. Perhaps. But what I saw with Elise, I saw happen to my own children. Much as my husband and I tried to make as normal a childhood for our children, it simply wasn't. In between ferrying my daughter to nursery school, my son to little league games and birthday parties, there were chemotherapy treatments. They were difficult but manageable. But there were also tears. I'm afraid I was not always as good at hiding things from them as I was from the rest of the world. My children soaked up my fears like sponges, and their body language at times spoke volumes about what was left unsaid.

My children are 18 and 22 now and I am well aware that in the scheme of things - I am a lucky duck as they say, 15 years this month post-mastectomy. I'm ok (though mentally, emotionally, some might tell you otherwise...) My kids are ok. But what I saw in Elise, I remember seeing in my own children, something I know often happens to children and siblings of cancer patients. I'm not sure you can put it into words; it's a certain look, perhaps it's sadness, or fear, or a loneliness of sorts. But you can see it clearly in the photographs. It's the weight of the world.

Robyn and her family just came back from a vacation to Hawaii courtesy of the Make-A-Wish Foundation. Robyn fulfilled one of her dreams to swim with dolphins during her trip. She has recently suffered a relapse and her family and doctors are in the midst of deciding whether to discontinue treatments. For the Brooks family, the weight of the world just got a lot heavier.

June 25, 2003

© Susan B. Markisz, Contributing Editor/The Digital Journalist

Kindly copy and paste the URL into a new browser:

http://digitaljournalist.org/issue0311/assign/markisz.html

Skin Deep: Courage and Hope against the Odds

By Susan Markisz

(Right) Sara Haghbin, with her adoptive father Bagher Harandi in their Scarsdale Home

Photos © Susan B. Markisz for The New York Times

SKIN DEEP: Courage and Hope Against the Odds

by Susan Markisz

Meet Sara Haghbin. At 14, her skin once again retains the softness and translucence of a newborn. Although the contours of her facial features are unlike those of any other 14-year-old, Sara's emotions, like any other teenager's, surface one moment and retreat to the recesses of her soul the next. The color of Sara's skin has the bronze richness of her Persian ancestry, while it also bears the imprint and color of her inherited new home: Scarsdale white. But any other similarities to Sara's privileged contemporaries end where Sara's story begins.

One afternoon when Sara was three years old, in a small Iranian village, a man harboring a vendetta against Sara's mother threw battery acid at her and her young daughter, forever altering the landscape of her face into a topographic map of injuries. While his vicious attack permanently killed Sara's mother's spirit, who is institutionalized, and injured herself, he blinded and physically damaged Sara's countenance, but he did not destroy her courage.

Last July, after languishing for years in a boarding school for the blind in Mashad, Sara became the adoptive daughter of Scarsdale residents, Bagher and Kojasteh Harandi, who had seen her two years ago, while on a visit to their native Iran.

When I arrived at the palatial home of the Harandis, Sara was upstairs in her room studying. I knew little of the girl's story, only the brief summary of the assignment sheet which had described her as disfigured, and that she was living with her adoptive family in Scarsdale. Bagher showed me an article that had been published in the weekly community paper a few days earlier. The paper had run a photograph of Sara, which was meant to shock, rather than to convey something of her personality.

14 year old Sara Haghbin was injured at the age of 3 when a neighbor threw battery acid at her and her mother during an altercation in their Iranian village.

Suddenly, Sara bounded down the stairs into the kitchen where she introduced herself to me. Her face, framed by a hijab, a Muslim head covering, didn't look anything like the photograph in the paper, and yet it almost defied description. We chatted for a few moments while I studied her face and thought about how I was going to make a portrait of her that was sensitive to her physical characteristics, yet true to her character. We often use soft diffused lighting when photographing certain older folks, women mostly, to maximize society's concept of beauty and minimize perceived imperfections, usually just nature's imprint denoting age and experience. But in this case, there was simply no getting around Sara's unique features. The face she had been born with had been all but obliterated by a cowardly act. She cannot breathe through her nose and although she is blind, she may be able to have corneal transplants in the future, allowing her some vision. Her skin, once wrinkled and dry, has become soft once again because of improved nutrition. Kojasteh and Bagher and several surgeons donating their services, have arranged for Sara to have the many surgeries she will require over the coming years, to reconstruct features of her face.

I felt I needed to get to know Sara a little better so I asked her to show me her room. She bounded back up the stairs and played a few notes on her electric keyboard.

A short time later, she sat down on the floor and showed me some large books and a machine resembling a typewriter, a Perkins Brailler. Sara, who had practically taken the stairs by twos, was almost completely blind and I hadn't even realized it! As she began making letters on the paper, with large tomes spread out before her on the floor, including books by Helen Keller and the Koran which she reads every day, she explained that there were still some phrases she didn't understand in English.

"Here," she said, gently taking my hand and placing my fingers on the tactile Braille words, as she read me the words she hoped

I could help her understand. Sara loves photographs, although she can't see them. "Susan is such a beautiful name," she told me, and I said: "Yes I like my name too, it's kind of old fashioned" and she added: "Like Sara."

She asked me if I had children and was excited to learn I had a daughter about her age. "She must be in high school," she said. When Sara asked me what she was like, my heart kind of skipped a beat as I skipped over details like Katie's cover girl face, gray-green eyes and long blonde hair. "She likes to ride horses," I said. "Oh," exclaimed Sara, "I love horses," and I told her that she would be right at home with Katie at the barn where she works and rides.

Our conversation was interrupted by a family friend, who came into Sara's bedroom to give her a stuffed Easter bunny. Delighted, she hugged her friend and the stuffed animal and I started to take some pictures. But the woman insisted she didn't want to be in the newspaper. "Better the parents," she had said. But Kojasteh had already said that she did not want her picture in the paper either, so I was kind of at a loss as to how I was going to show the relationship of this child to others in her new family.

14-year-old Sara Haghbin, with her adoptive father Bagher Harandi in their Scarsdale home. The Harandi family has said they will pay for the dozens of operations necessary to reconstruct her face and restore some of her eyesight.

Writer Lynne Ames had arrived and I knew she would want to talk to Sara. We had been upstairs for quite awhile, so we went downstairs where, surrounded by her new family, a reporter, a photographer and a family friend, she recounted some of the horrors she had experienced as a young child. In English and Persian translated by Kojasteh, she told of people running from her in horror, stories of cruelties and insults, which she has endured throughout her life. Her stories were heartbreaking except for the fact that somehow Sara has been able to accept people the way they are even if it's not always mutual. "There is always hope," she said, "that's what keeps me going," as she segued into her future career plans, as an attorney "to help people". She attends the New York Institute for Special Education in the Bronx, where she has many friends.

I still didn't have any photographs of Sara with anyone from her adoptive family. The Harandis three daughters, all in their twenties, were at work or away at college. I felt impeded by Kojasteh's modesty about appearing in the photographs and the reticence of their family friend to be in the photographs as well, even as I noted their keen interest in her welfare. Perhaps it was a cultural thing that I didn't understand. I don't know, but it was hard not to wonder. After several hours, I realized my photograph would probably be one of Sara alone. There simply was a missing piece to this picture and I keenly felt the absence of the kind of emotional connection that is an intrinsic part of what I look for when photographing people.

Finally, I had promised that I would take a few pictures of the family and their family friend, as they had requested, out in Kojasteh's lush botanical garden, filled with splendid orchids and exotic plants. I first photographed Sara with Kojasteh's friend who had given her the Easter bunny.

There was genuine affection between the two and I felt conflicted---happy to have observed this emotional interaction, yet somewhat resentful and deprived at not being able to use the photographs illustrate it.

Just before Bagher and Kojasteh came into the garden to be photographed, Sara picked up the Easter bunny and tossed it gleefully up in the air several times, catching it and hugging it tightly each time. Although I had managed to capture Sara's youthful enthusiasm and playfulness, in some ways, I felt sad that one of my best pictures depicted Sara with an inanimate object.

Sara had told me earlier that being interviewed and photographed for the newspaper was exciting. "It must be a very big newspaper," she laughed, referring to the amount of time Lynne and I spent there, and the number of times she heard me press the shutter. She loved the attention. I couldn't think of any single person that I've ever photographed in my entire life, less concerned about how she would be portrayed in the photographs. Sure, she is blind. But she also understands the meaning of the words: skin deep.

© Susan B. Markisz, Contributing Editor/The Digital Journalist

Kindly copy and paste the URL into a new browser:

http://digitaljournalist.org/issue0105/assign/Markisz.htm

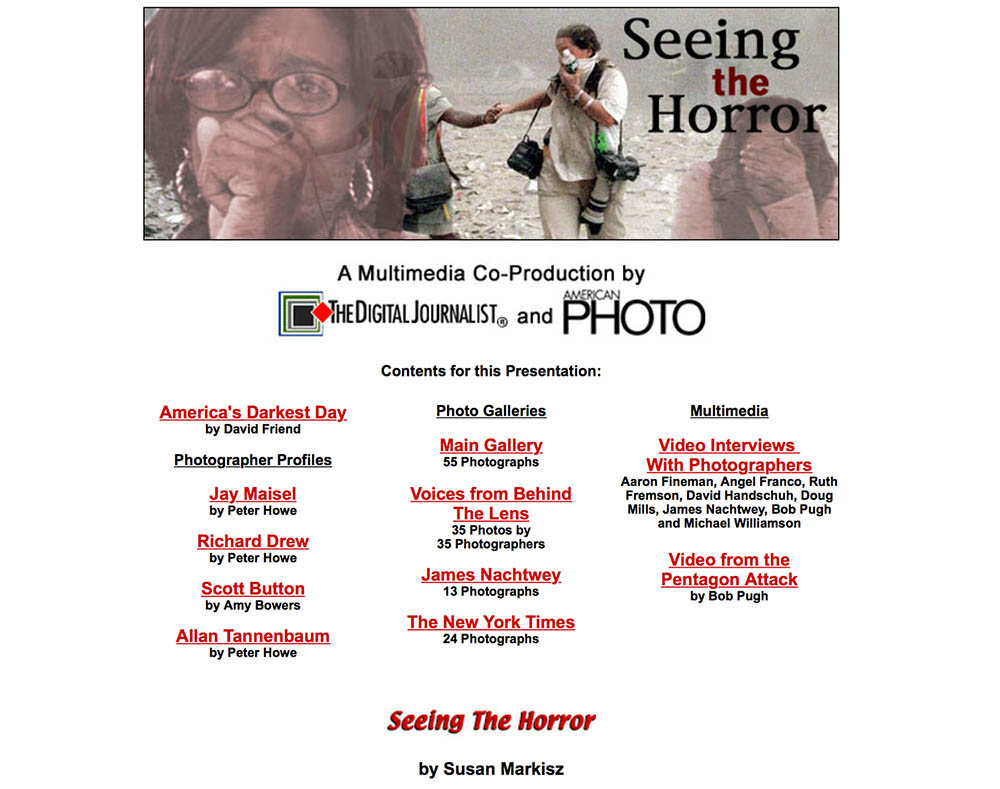

Seeing the Horror

By Susan Markisz

Seeing the Horror: The Digital Journalist Multimedia Cover Story, October-November 2001. I wrote and co-produced this multimedia presentation and cover story which included video interviews with photographers who covered the 9/11 terrorist attacks, providing an important historical perspective of and by photojournalists who not only covered the tragedy but who were victims themselves. This two-part series won an Online Journalism Award from Columbia University for ‘Excellence in Writing’ and an Honorable Mention for Multimedia in the National Press Photographers Association 2002 Pictures of the Year.

News Photographer David Handschuh has been running after New York stories for the past twenty years. But on the morning of September 11, the story he was pursuing sent him running for his life. For Handschuh and other photographers, the day began as an ordinary workday. Some were deployed throughout the city covering the mayoral primary while others were visually taking the City’s early morning quotidian pulse.

At 8:46 a.m. the ordinary became the extraordinary as voices over police and fire scanners reported ominous sounding information of what was first assumed to be an errant private plane hitting the north tower of the World Trade Center. Moments later came terrifying details of a second plane, a commercial airliner slamming into the south tower, sending photographers into combat mode, scrambling to find the quickest route downtown. Within minutes, photographers who had made their way to the scene, found themselves in mortal danger along with firefighters, police and rescue workers. Within the hour, photographers were wiping away tears, while at the same time producing stunningly surreal images, destined to become embedded in our national collective psyche. By the end of the day, the New York primary had become a footnote---history deferred---to an ignominious terrorist attack on New York City’s World Trade Center, leaving more than 5,000 dead or missing, and injuring thousands more.

In a city where local photographers are often grounded on national news stories, New York City became the literal and figurative epicenter. As iconic twin towers symbolically---and now precariously---stood guard at the southern tip of Manhattan, photographers going about their daily assignments were reassigned to an unfolding disaster of epic proportions. Local news was eclipsed by a monumental human toll, buried underneath twisted steel and wreckage. Wire services transmitted images almost instantaneously to a world in shock and newspapers and magazines produced comprehensive visual editions of the attacks on the World Trade Center. The New York Times produced a special section called “A Nation Challenged” devoted to continuing coverage of the Word Trade Center attacks and the aftermath. Time, Newsweek and U.S. News and World Report each produced special editions that sold out almost immediately to a citizenry that needed visual acknowledgment that the unimaginable actually did happen.

With the country in mourning, photographers on the front lines quietly produced some of the most astonishing images the world has ever seen; astonishing in part because of the nature of the tragedy; in part because of the speed of dissemination, in part because photographers were eyewitnesses to events as they unfolded, not only as after-the-fact documentarians. Two photographers lost their lives, others faced life threatening injuries and many, perhaps not surprisingly, have experienced emotional trauma.

Handschuh, a staff photographer for The Daily News, was scheduled to teach a graduate class in photojournalism at NYU in the morning, and cover late election results at night for the News. While cruising around Manhattan’s West Side on his way to class, he heard voices from Manhattan Fire on the scanner screaming to send every piece of apparatus available to the World Trade Center. As W. 43rd Street’s Rescue One rushed southbound, Handschuh swerved across the traffic island on the West Side Highway, and followed them on their rear bumper, observing their preparations as they threw on their packs, readied their oxygen tanks, and placed tools in their bags. Handschuh remembers several of the men waving out the back door to him as he took their pictures. They may have been the last images taken of Rescue One, who were among the first responders to the scene. Fire Department officials have confirmed there are thirteen dead of Rescue One’s twenty-five members, including two officers.

With massive destruction looming ninety floors up, people on the street did not yet seem to be conscious of the horror unfolding above them.

“It was eerie and quiet,” said Handschuh, describing the moments after he arrived, just before the second plane slammed into the south tower. “People were coming to work with their coffee and danish, just standing and watching. You could hear the flames crackling, glass breaking, you could hear things falling. But it was like someone had turned the volume off on the usual hubbub of the city, like someone had hit the mute button.”

Handschuh himself had no inkling of the danger he was in until several moments later. “I had no idea I would be running for my life as a 110 story building was bombed by terrorists,” he said. Turning his lens on the flaming tower, Handschuh realized that not all the debris falling from the north tower was glass and metal. “I couldn’t begin to describe what it looked like,” he said, referring to people who appeared at the windows and in desperation began to jump to their deaths rather than be burned alive, a sight and sound Handschuh says he will never forget. He has no recollection of making the picture that appeared in the Daily News, a photograph taken moments after the second plane hit the south tower. Standing directly underneath the World Trade Center, the photograph is framed by an achingly beautiful blue sky as an ominous black cloud of smoke billows out, and a brilliant orange fireball at the top spews glass and melting steel to the ground.

“...in the back of my mind I heard a voice that said: ‘run, run, run, run.’ I’ve been doing this for 20 years and I’ve never run.” ~David Handschuh

If the desire to flee in life threatening situations is strong, the desire to stay and document them for news photographers, is often stronger. While Handschuh stayed long enough to take some pictures, at some point his instincts kicked in. “Time stood still,” he said, as he looked up to see the south tower begin to disintegrate, accompanied by noises that he said sounded like high pressure gas explosions. “My initial reaction was to grab my camera, to start taking pictures,” he said, “but in the back of my mind I heard a voice that said: ‘run, run, run, run.’ I’ve been doing this for 20 years and I’ve never run.” He is convinced that listening to that voice saved his life.

Still photographer Bill Biggart and Glenn Petit, a cameraman for the NYPD were not as fortunate. Biggart was killed in the collapse of the towers and Petit is missing and presumed dead. Moments earlier, Handschuh had run into Petit who told him he had “unbelievable footage.” Of that moment, Handschuh said: “We gave each other a hug and said ‘be careful,’ as Glenn ran east, and was not seen again.”

Handschuh escaped with his life but was seriously injured. Describing the vortex that swept him up in the collapse of the south tower, he said:

“The wind that picked me up was like getting hit in the back by a wave at the beach that was made of hot gravel, like being picked up by a tornado. All of a sudden I was flying, with no control over direction.”

He did not lose consciousness, but he was thrown a full city block by the force of the implosion, landing underneath a vehicle, trapped by debris, which crushed his leg, breaking it in three places. Three firefighters rescued him, taking him to a delicatessen near Battery Park City, only to be caught underneath the deli’s caved in façade when the second tower collapsed. “There were grown men inside, holding onto each other for their lives, some calm, some screaming with just the desire to live, pushing their way out of the debris.”

Shortly afterward, fellow Daily News photographer Todd Maisel photographed Handschuh’s rescue by a paramedic, a cop and a firefighter as they removed him to a police boat on the Hudson. Although Handschuh lost his glasses, cell phone and pager, he managed to hold onto his cameras until shortly before he was transported to Ellis Island on a police boat.

“There we were,” said Handschuh, “under the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, breathing, entire huddled masses, yearning to break free, the smoke from the destruction, a symbol of New York, a symbol of the United States, a symbol of the American economic system in ruins…And I didn’t have a camera.”

New York City’s news photographers were on their mark on September 11. There is no lack of apocalyptic imagery of suicidal bombers hitting their targets. In stunning images of almost architectural grandeur, there is Steve Ludlum’s perfectly composed image of twin monoliths, breathing dragons of fire, with the Brooklyn Bridge as a defining element in the foreground, an image which appeared on the front page of the New York Times on September 12. There is Lyle Owerko’s photograph, which appeared on the cover of Time’s September 11 special issue, taken at virtually the same moment, from the west side, underneath the towers. In Washington, D.C. there is Jim Lo Scalzo’s image of the Capitol shrouded in fog from the burning Pentagon in the foreground. In what at first glance appear to be stills from a Hollywood special effects movie, there are Robert Clark’s series of four horizontal images taken shortly after the first impact. Against a perfectly blue sky, as the north tower burns in the first image, a menacing commercial airliner threatens the south tower in the second, and in the third and fourth images, the plane slams into the south tower, creating indelible reminders of vulnerability.

As photographers focused on the heavily damaged towers, there was a sense of unreality to the attacks. The towers no longer seemed invincible but down on the ground, camera lenses began focusing on the human dimension, the impact of which was not yet fully comprehended. As people leapt to their deaths from the burning towers, photographers ’s Richard Drew/AP and The Daily News’ Susan Watts made those images, necessary to the telling, and controversial in their publication. Some editors came under fire for reproducing images that depicted such immense suffering. Drew’s image of a man in an upside-down free fall, juxtaposed against the tower, almost looks like he could have been tethered to a bungee cord. Sadly, he was not.

The "Dust Lady"

Yet for all the long lens images that suggested what was happening at a distance, there were images in which the photographers’ proximity to suffering told a profoundly personal story: that this was painfully close to home, images in which survivors’ eyes or body language revealed what they might have been feeling, or thinking at that moment. Stan Honda’s unforgettable photograph of a woman coated with the pulverized remains of the World Trade Center, shrouded by a cloud of otherworldly toxic yellow dust. She stares directly at the camera in confusion and supplication. Perhaps even defiantly, she seems to ask: “Do you understand this? Because I simply do not.”

Shannon Stapleton photographed a mortally wounded Father Mychal Judge, chaplain of the New York City Fire Department, who died as debris collapsed on him, shortly after giving last rites to a firefighter. The peaceful look on Father Judge’s face belies the surrounding mayhem and the anguished look on the five men’s faces who are carrying him out of the debris. Honda and Stapleton’s images have an intimate human dimension to them, in a way that Ludlum’s and James Nachtwey’s images, respectively, of the collapse of the towers and the ethereal remains of the World Trade Center, now known as Ground Zero, speak to the enormity of the physical dimension.

Also at eye level, are the following memorable images: Angel Franco’s close-up of women reacting to the horror on the street, one woman with her fist clutched tightly up to her face, the other covering her eyes in disbelief; Daniel Shanken’s photograph of people fleeing their city over the Brooklyn Bridge, surrounded by an almost palpable thickness of gray ash and dust, one can almost feel its weight; Todd Maisel’s photograph of weary firefighters on top of the rubble with eerie remnants of steel beams as memorial at Ground Zero; Justin Lane’s image of a man being triaged by firefighters and EMT’s with an exhausted firefighter leaning against the subway entrance. It looks like the end of the world; Suzanne Plunkett’s image of the dust cloud chasing terrified pedestrians as the towers fell; Ruth Fremson’s woman in red: red hair, red dress, her limbs bloodied from injuries, sitting on a sidewalk, terrified, startled, fragile; Catherine Leuthold’s photograph of a determined rescue worker whose eyes and face are encrusted with ash, with what appears to be a tear streaming down his face; Susan Watts’s photograph of a dazed man whose shirt is caked with blood, being aided by a man on a cell phone; Amy Sancetta’s photograph of a businessman and woman carrying briefcases covered in dust and ash, fleeing the capitalist marketplace, as if in subjugation to the terrorists’ unspoken goals. If there is defiance in some of the photographs, there seems to be resignation and abject fear in others.

These images confirmed America’s worst fears: that what was lost were not simply American icons reduced to rubble; but rather what Americans held most dear: mothers and fathers, sisters, brothers, aunts, uncles, children, and, if you will, innocence. Photographers used to being the ultimate observers, perhaps for the first time, found that it was impossible to separate themselves from the story. The emotional distance photographers have often called upon to maintain a feeling of objectivity for their stories, disappeared along with the thousands of other victims in the wake of the tragedy.

Symbol of Hope

At a time when Americans needed a small sign of hope, Thomas Franklin, staff photographer at The Record in Bergen County, NJ provided an image that is already being compared to Joe Rosenthal’s photograph of Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima, an image that Franklin made of three New York City firefighters raising the American flag on Ground Zero. Franklin, who has received thousands of phone calls and hundreds of emails, “mostly from complete strangers around the world" telling him what the photograph means to them, said he is hopeful that money can be raised from the sale of the photograph to help victims. “That speaks to me about the immense power of photojournalism,” he said.

Photographers attempting to document the attacks confronted more obstacles than debris and the cyclone fence that was eventually constructed around the fallen towers. Not only did they meet with some of the typical resistance from the New York City Police Department, but some were arrested for criminal trespass as well, leading some to speculate if press credentials were worth having. The first few days were so chaotic that anyone who wanted to find a way into the site to photograph, could do it with a little persistence. Carolina Salguero, a photographer whose work was published in The New York Times Magazine on both September 16 and September 24, managed to get to Ground Zero relatively quickly the first day by coming over in her boat from Brooklyn. But as time wore on, access to the site became more difficult as the Police department and National Guard threatened anyone with media credentials with arrest even if they took pictures from behind the fence. While there was an understandable need for FEMA and the NYPD to secure the area, the public seemed to have as much access as those with legitimate media credentials, angering many photographers and forcing some of them to find creative ways of getting to the site. Some photographers were reported to have impersonated firefighters and construction workers, leading to dozens of arrests of media personnel by the NYPD. Many photographers have voiced loud opposition to photographers who misrepresented themselves, ultimately making it more difficult for those who used legitimate means and current credentials to get their pictures. Unfortunately for many who went through DCPI channels, getting close to the site meant waiting hours to perhaps get only a block or two closer than the so called “media villages” established by the NYPD.

Although closure seems elusive for Americans in general and New Yorkers in particular, photographers who were involved in covering the World Trade Center attacks, have expressed anguish about the people they have photographed and the stories they have covered. New York Times staff photographer Ruth Fremson, who was stationed in Jerusalem for the Associated Press before coming to the Times, has seen destruction on a massive scale, but “never at a moment when so many people were destroyed.” Like David Handschuh, Fremson was caught in the tidal wave of the two buildings’ demise but emerged uninjured. She said she is haunted by pictures she took, of people helping others, not knowing the outcomes of some of the rescue efforts. Fremson received a phone call from the parents of the woman in red who appeared on the front page of the New York Times, updating her on their daughter’s progress. “Knowing that people are safe is a huge relief,” she said.

In a twist of irony, Washington Post photographer Michael Williamson found the tables turned on him while covering the emotional stories of people searching for missing loved ones. “I was talking to a woman who told me the story of being on the cell phone with her daughter when her daughter died; her daughter couldn’t breathe, and then silence because the building collapsed,” he said. “I just started crying, and then another photographer photographed me thinking I’d lost someone. I was just upset for all these people who have lost loved ones,” he said.

Photographers have been profoundly affected by the World Trade Center attacks. Veteran New York Times staff photographer Angel Franco, who was in Kuwait, and who has seen smart bombs and terror overseas, worries that none of the young photographers who have covered the events of the past few weeks are prepared for the emotional fallout that will follow. “None of them is combat trained,” he says.

“I have this vivid picture that I haven’t been able to shake out of my head, of bodies beneath the wreckage. It was too much for me the first time.” ~Aaron Fineman

Freelance photographer Aaron Lee Fineman, who was assigned by the New York Times to take pictures on the night of the attacks, spent from 9pm until early the next morning documenting rescue efforts amidst the rubble. His photograph of workers moving wreckage during a rescue effort, ran on the front page of the New York Times on September 13. During the night, he was grazed on the back of his head by falling debris and his digital camera was slightly damaged. Fineman voiced concerns as a freelancer who pays for his own health and equipment insurance, a not insignificant consideration for a person who risked his life in the pursuit of his job. Assigned to return the following night, he initially said yes, but then had a change of heart and decided to turn down the assignment. Finding the experience turbulent, Fineman said: “I have this vivid picture that I haven’t been able to shake out of my head, of bodies beneath the wreckage. It was too much for me the first time.” Fineman credits Angel Franco, who has spent time talking to Fineman, with helping him to get through some of the trauma.

The conflict of whether to stay or to get closer was described most poignantly by Helayne Seidman, a freelance photographer who works for the New York Post.

“I was shooting on Broadway near Fulton Street,” she says in her contribution to ‘Voices.’ “My first thought was, ‘Should I stay or should I run?’ I instinctively ran from the dust ball because I could not breathe. I feared the other tower might collapse, so I covered the exodus of people, rather than going back closer. The conflict of whether I should have gone back has haunted me all week.”

Surely Seidman made the right choice, but the need, as a journalist to get images that were in some ways not only difficult to make, but in some cases under life threatening circumstances, have made photographers ask themselves many questions: Why did I survive when so many others didn’t? Why didn’t I get the pictures when I had the opportunity? Why wasn’t I there? There were many photographers who for personal or professional reasons, were unable to cover the story and are having a hard time dealing with not having gotten images from perhaps the biggest story New York has ever seen, a trite quandary, to be sure, when compared to life’s bigger issues of life and death, but one with which many are nonetheless grappling.

Emotions Beneath the Surface

The visual testimony of photographers who have worked on this story has been remarkable. But for many, the tears are just below the surface. Mel Evans, a staff photographer for The Record, in Bergen County, New Jersey says he’s done “much better working than not,” but says when he arrives home at night he hugs his daughter just a little tighter. Shannon Stapleton, chokes back tears when he thinks of the photograph he took of Father Judge being removed from the rubble. But he takes some solace from a letter he received from Judge’s family thanking him for taking such a compassionate photo, telling him: “It helps to know that he died doing what he loved best, helping his beloved firemen and the citizens of New York City.” Stapleton says he is heartened knowing that a photo could have a positive impact amidst such horrific destruction.

Photographers can be proud of their work documenting history over the past few weeks. But David Handschuh, now recovering at home after surgery, urges them to be mindful and take a few minutes to assess their psychological well being after witnessing the attacks. He says it is not normal to see the kind of horror that many experienced first-hand while on the job.

“Whether it means talking to a friend, clergyman, psychologist or psychiatrist, it may be necessary to get some kind of stress debriefing,” he says, adding that the outpouring of support from friends and colleagues in visits, phone calls and emails have raised his spirits and helped enable him to move forward. He acknowledges that although newspeople often find it easier to talk to a colleague, at least initially, it is not unusual for peer support to act as a springboard for clinical support where needed. Two years ago, the NPPA, of which Handschuh is past president, conducted a survey of about the effect on newspeople of covering traumatic situations in doing their work and found it was not unusual for visual journalists to suffer negative effects from the cumulative exposure of repeatedly documenting the news. Newscoverage Unlimited, a not-for-profit organization established in 1999, is working together with NPPA on this initiative to assist visual journalists in fostering mutual support through trained peer counselors. They are in the process of setting up a New York office and a nationwide support network to deal with the problems that will undoubtedly resonate for a long time as a result of the World Trade Center attacks. For peer support and information, journalists in need of support may wish to contact NPPA/Newscoverage Unlimited at [email protected] or to get a complete list of trained peer counsellors that journalists can call with issues relating to work related traumas, go to: http://www.nppa.org/wtc/help.html. For general information as to how news organizations and individuals can volunteer and support their ongoing efforts, contact [email protected]. The Dart Center also has a message board set up for journalists who have experienced trauma in their work at www.dartcenter.org.

Photographer David Handschuh is taking things one day at a time. People have asked if he intends to keep on taking pictures and his answer is “probably, yes.” He insists that “we will get over this,” adding “we will be changed in ways that we never imagined. But we will be stronger and more tolerant. Just looking out the window at the blue sky makes me happy. I am here.”

October 1, 2001

© Susan B. Markisz, Contributing Editor/The Digital Journalist

Kindly copy and paste the URL into a new browser:

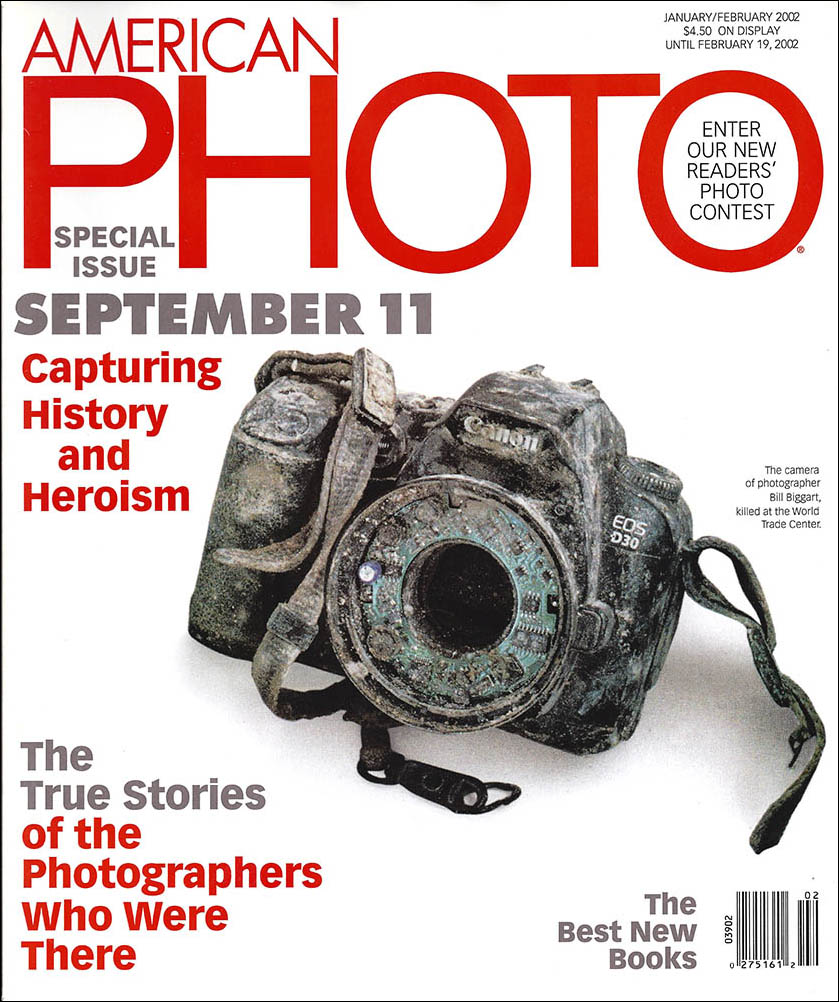

SEPTEMBER 11: CAPTURING HISTORY AND HEROISM A Collaboration between AmericanPHOTO and Dirck Halstead, Susan Markisz and Peter Howe of The Digital Journalist

One was at a polling station in Flushing Queens, photographing early-morning voters in New York City’s mayoral primary. Another was shooting models backstage at a maternity fashion show in midtown Manhattan. One had just stepped from his shower when the telephone call came in: A plane had hit the World Trade Center. All of these photographers made instantaneous decisions – decisions that would set their worlds spinning and place them in peril. By car, by subway, by bicycle, and by boat, they went to record an atrocity they would scarcely imagine.

On the following pages, you will find their stories. In the week following the September 11 terrorist attacks  on New York and Washington, D.C., American Photo magazine joined with the distinguished Webzine called The Digital Journalist (digitaljournalist.org) in a special project to document the experiences of the professional photographers who rushed to Ground Zero in New York to make pictures, in some cases just minutes after the attack began. The project, involving hours of interviews done while the photographers’ memories were still vivid, was a unique undertaking, and we have devoted

on New York and Washington, D.C., American Photo magazine joined with the distinguished Webzine called The Digital Journalist (digitaljournalist.org) in a special project to document the experiences of the professional photographers who rushed to Ground Zero in New York to make pictures, in some cases just minutes after the attack began. The project, involving hours of interviews done while the photographers’ memories were still vivid, was a unique undertaking, and we have devoted

a major portion of this issue to it.

Photojournalist Dirck Halstead, the founder and publisher of The Digital Journalist, was quite correct in his assessment that the pictures produced by photographers that day rank among the best and most daring in the history of the medium.

Journalists at newspapers, magazines and photo agencies rose to the occasion. The accounts of these people explain much more than simply how they did their jobs, however.

They reveal very dramatically the deep-grained journalistic instincts that animated these men and women – an instinct fed by the underlying belief that the telling of history matters.After September 11, America and the free world were stung by the sights these photographers brought to them. We were also uplifted by the heroism and sense of dedication framed in the images. Photographers of all kinds can be uplifted as well by the professionalism shown by the people featured in this issue.

We would like to thank The Digital Journalist’s crew, including Halstead, Susan Markisz and Peter Howe, for their work on this project. We also offer our condolences to the family of Bill Biggart, the only professional photojournalist killed while covering the collapse of the World Trade Center, and to the families of all the victims of the attacks.

See publication: AmericanPHOTO: Capturing History and Heroism

Getting Beyond the Headlines

By Susan Markisz

A multimedia interview with Photojournalist Ami Vitale for The Digital Journalist

Photojournalist Ami Vitale is on the road less traveled. Often unpaved, and at times dangerous, that road has taken her in the last three years, to places of surreal beauty and civil unrest. It has also taken her to places where there is extreme poverty and horrible destruction of life and property, and to villages where there is no running water or electricity, places she describes as “worlds apart.” But it is not the differences that have drawn Vitale to them; it is the commonality of human emotions and life experiences that have irrevocably bonded her with the people she has photographed in them.

Vitale’s photographs have appeared in Time, Newsweek, US News & World Report and The New York Times, among others and 2 stories, which she completed in 2001 in Guinea Bissau and Mauritania, placed first in the National Press Photographers Association Best of Photojournalism. In 2000, Vitale was the recipient of several grants, including one from the Alexia Foundation, which enabled her to travel to Africa to work on a story she called “Notes from a Mud Hut.” The story had germinated in 1995 while visiting her sister who had been living in Guinea Bissau while working for the Peace Corps.

After receiving the Alexia grant, she returned to Guinea Bissau in 2001, where she thought she would stay two or three months, but ended up staying six. “It helped me to realize what I wanted to do with my work,” said Vitale, “and that is to get beyond the headlines, to show how the majority of people live on this planet. As soon as you get off that paved road and into the villages, it’s a marvelous life,” not an easy one, she insists, but one that calls out for understanding and compassion, if for no other reason than to dispel misconceptions and to foster an awareness of distant cultures.

Initially she had intended to cover the effects of the war on the people of Guinea Bissau, but the idea changed dramatically once she arrived. “In fact, the people had adapted quite well, and the effects of it were almost impossible to see,” said Vitale. Instead, she lived in the village of Dembel Jumpora, in a mud-hut with a woman named Fama Jamanka and her children, photographing daily life, becoming intimately involved in the daily routines of the village and learning to speak rudimentary Pulaar. Far from the comforts of home, the bed she slept on was made of sticks and hay, and Dembel Jumpora had no running water. “It was pretty funny,” she remembered, “the kids asked me why I did not pull the water out of the well quickly. And then I had to explain that we just had to turn a switch to get water and they were amazed.”

Vitale’s photographs transcend the ordinary glance; they are filled with an intimacy and insight that does not come from simple observation. Amy Vitale is not the proverbial fly on the wall. She does not simply report her stories. She lives them. While the journalist Vitale likes taking pictures, she cherishes the life experiences as much as getting them on film. “It almost had less to do with photography; it was a whole other look at Guinea Bissau,” she said. “They taught me everything from learning to carry water in buckets on my head to laughing in the face of some terrible stuff.”

When Vitale wasn’t taking pictures, she was collecting such food staples as cashews and mangoes and water, washing clothes, playing with the children and going to ceremonies… “lots of things and nothing at the same time,” she said. “Much of life was ceremonial…every week there was a funeral, or a wedding, teenage weddings…and male and female circumcisions.” Her pictures of a female circumcision may make people shudder but she takes a different view. “At first I was horrified… but we take things out of cultural context. It is horrible, but I left with the understanding that we can’t go in and change these rituals. If you want to do something, start helping people by paying more for their crops. I think you have to start with bigger issues. I remember reading a WTO document on the cashew market and knowing before they did, that the cashews were going to fetch them half of what they got the year before. People were excited the cashew season was coming because it was the end of the dry season and there was no food left in the village. But it made my heart sink knowing they would be getting half of an already abysmal price for their hard work. They are in such a vulnerable situation and the odds are against them. In the end, it was terrible to watch how little they made for their perishable goods like mangoes, cassava, rice and cashews, and how much they had to pay for the things they need…like life saving medicines for curable diseases like malaria.”

Vitale believes that by spending time on a story, and by living with the people she photographs, it has helped her to get beneath the surface of a story. “You have to get into a culture to actually live there to understand things aren’t as sensational when you understand them in their context. I’ve jumped in, parachuted into a few places before and I didn’t like it. It’s very dangerous and I’ve felt like I wasn’t portraying things truthfully, or it was a different truth.”

Vitale began her career in photography after graduation from UNC with a degree in International Studies, by working as a picture editor for the Associated Press in New York and Washington, D.C. But it wasn’t long before she decided she wanted to start taking the kinds of photographs that were on her computer screen. “I can actually remember the day,” she said, “seeing some pictures coming in from the Balkans and being really moved.”

She saved money by working overtime at AP on the desk until 1997, when she moved to the Czech Republic where she began traveling throughout Eastern Europe and Africa. “I saved money, am single, have no family, no responsibilities, so I tried doing little feature stories, writing and trying to sell photo packages to newspapers, just to break even. In Angola, nobody was interested in the ongoing war, so I found little sidebar stories like the oil expats [sic] and a bunch of French surfers living in a war zone… anything to break even.” Although she says has difficulty editing her own work, she adds “it was great to begin editing because it allowed me to understand how the industry works and what editors in New York and Paris were looking for.”

Now 31 and based in Kashmir, India, she is working under contract for Getty Images and also does work for several NGOs, which have also supported her work on the kinds of stories she is passionate about in places like Kashmir and Gujarat which are very meaningful for her. Her often lush and compelling images of Kashmir belie the tensions and violence that are just beneath the surface. While the United Nations calls Kashmir the most dangerous place on earth, Vitale says it’s a misconception. “The people are warm and wonderful. The majority are not militants; the majority of people are not terrorists; they’re just trying to have a life. What’s happening there is very sad; they’re caught between something that is much bigger than they are. Sadly, journalists love it there. You go to these places, it’s not St. Tropez, but the people are great, they want to be heard, they want the terror to stop.”

Vitale gets very emotional about the violence and bloodshed that she witnessed this year in India’s riot torn western state of Gujarat, a conflict borne out of religious hatred between Hindus and Muslims. But she feels that it is an example of how the media can effect positive change. “The media really influenced the government to take action and stop the violence which was brutal. It hasn’t gone away, but the government has taken steps that they never would have without media attention.” Vitale feels it is important for journalists to think about the implications of their images, how they are being used, and to make sure they are not sensationalizing things. “To be honest,” she says, “the more I do this, the less I do it for photography’s sake. I love photography, but it’s more about what’s happening. I wish I were a better writer, or poet or musician, to use some other way to use my experience to move people. We’re at a crucial time in the world, so polarized, with such a lack of understanding. The pictures themselves have power, but I don’t want to do it to make nice pictures.”

Vitale feels that it’s important to bridge cultural gaps and although she can understand why someone in Kansas City might have little interest in what’s happening halfway around the world, she thinks it is important.

“In my personal viewpoint, I feel like even though you can’t see it, everything is really connected. I see a ripple effect…for example, people are paying $8.00 a pound of coffee and yet in Kenya people are going into debt that are producing it. And the violence…all of these things affect us. People feel hopeless like they can’t do anything about it, but they can do a lot by understanding, by reading through the headlines, by being a little more compassionate.”

To young photojournalists who are concerned that these kinds of stories can’t be done, or that there is no interest, Vitale’s response is to “keep going.” I hear people saying ‘don’t go there, nobody cares about it; can’t be done.’ Maybe it won’t be in National Geographic, but save some money, find a niche; research a story and if anything you’re going to get so much out of it. The experience is great. I want to be a more positive voice for the industry. I truly believe that everybody has a voice; everybody has something to say. We all do this for personal reasons,” says Vitale. Of her experience in Guinea Bissau, she says she is grateful. “I miss the simple ways and how they look at life. I think of them often, every time I see a full moon, it makes me think of my last night there when they asked if we had a moon in America. I loved that I noticed time moving by the moon and the seasons. There was no future for me, just day to day. I think it helped me see things and my life in a radically different way. I don’t know if it’s possible to get to a truth, but I’m searching for that.”

© 2003 Susan B. Markisz, Contributing Editor/The Digital Journalist

Kindly copy and paste the link into a new browser window

http://digitaljournalist.org/issue0301/av_intro.html

Putting the Media in Soldiers' Shoes

By Susan Markisz

A comprehensive look at the Pentagon-sponsored embedding of media during the Iraq war, from the perspectives of the Pentagon, media outlets and independent photographers.

It was a daring experiment. Embedding journalists with troops during the war in Iraq is not the first time the United States government capitalized on the American media to try and influence public perception. But for the first time in history, the Pentagon hammered out an ambitious agreement with media bureau chiefs representing national and international media, designed to give journalists unprecedented access to daily combat operations in Iraq, with minimal restrictions.

In a telephone interview on May 6, Bryan Whitman, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs, and one of the co-authors of the plan, addressed the motivations for the embedded journalists plan.

“As the potential for military action increased, there was a conflict on the horizon,” he said. “We were getting information from media managers and reporters that they wanted to cover alongside the troops, up close and personal and we needed to find a way to bridge that gap while protecting our position.”

One of the factors that ultimately motivated the Pentagon to allow embedded journalists was Saddam Hussein himself. “Our potential adversary was a practiced liar, who used deception to fool the world community and what he was up to. The question was how to mitigate,” said Whitman. “We believed by putting a trained observer in the field---which I think is the definition of a reporter---to report in near real time, we could counter some of the disinformation coming out of the Iraqi Ministry of Defense.”

Shaping Public Perception

In its official policy, posted on the Department of Defense website, The Pentagon acknowledged that “media coverage of future operations will to a large extent, shape public perception of the national security environment now and in the years ahead.” (www.defenselink.mil/news/Feb2003/d20030228.pdf) (Note this Pentagon link is no longer live)

While the embedment process offered narrow coverage from a particular vantage point, it offered reporters the opportunity to develop close relationships with the troops and therefore the ability to report in depth from that position. “We are proud and confident in the professionalism and experience of our forces; how well-trained, equipped they are; and the dedication and care used to execute their duties to avoid collateral damage,” emphasized Whitman. “It was a good way to let Americans and the world community witness what our troops do. In our experience it is inescapable that after spending some time with our troops, reporters would see their professionalism and determination.”

On the surface, the results of this broad experiment appear to be a win-win situation for all concerned. But further review may yet determine whether agreement to restrictions in the Pentagon policy hindered journalists or compromised their objectivity, whether the embedding process lived up to expectations of journalists and their media affiliations, and whether accredited unilateral journalists encountered difficulties because of the choices they made.

From a content perspective, what resulted from embedded photojournalists was no less than a riveting portrait of the U.S. military during combat in the war in Iraq, with journalists reporting and photographing alongside troops as they advanced on Umm Qasr, Nasiriya, Basra and Baghdad. There were spectacular images from journalists representing many media organizations. David Leeson and Cheryl Diaz Meyer, staff photographers with the Dallas Morning News, were embedded with the Third Infantry Division and the U.S. Marines of the Second Tank Battalion respectively. New York Times staff photographer Vincent Laforet, embedded on the USS Abraham Lincoln, produced stunning images of night time sorties, life on the flight deck, and feature stories below decks, reproduced in the New York Times 16 page daily Nation at War section, with some images running 24 inches across the page. Todd Maisel, of the New York Daily News, embedded with the Seabees, spent most of his six week assignment in a waiting game, laden with NBC gear, 3 cameras, lenses and laptop, for a combat assignment that never happened, photographing instead, Seabees engaged in a variety of humanitarian and support activities. There was no provision in place for a journalist to switch to another unit, to go off in pursuit of another story and return to their unit, something that would have been highly impractical, given the logistics involved, but it might have made the idea more palatable for those who wished to have a little more flexibility in their reporting.

According to Navy Chief Petty Officer Diane Perry of the Defense Department, there was a broad range of media representation. “The Department of Defense issued invites for more than 800 embedded media positions, of which more than 600 were deployed from 220 media organizations,” she said. “70% of media allocations were slated for domestic national print and electronic media, 20% for international media representing more than 60 countries in Europe, Asia and South America, including news agencies such as Sky News and Al Jazeera, and the remaining 10% of the embedded positions were allocated to local and regional media.”

The experiment could have gone horribly wrong for both media and military, had the outcome not been swift and casualty numbers low. But a quick glance at some of the headlines in the Nation at War section of The New York Times, revealed that the story of embedded media covering the war in Iraq was almost as big as the story of the war itself:

Reporters Respond Eagerly to Pentagon Welcome Mat; In Europe, War Coverage is Everywhere, All the Time: Page B3 March 23, 2003; Television Producers are Struggling to Keep Track of War’s Progress, or the Lack of It, Page B14, March 26, 2003; Hot Disputes over Images of POW’s Held on Each Side, Page B6, March 26, 2003; Reporters New Battlefield: Access Has Its Risks as Well as Its Rewards, Page B2, March 31, 2003; News Organizations Remove Some Reporters from Units – Reassigned to Begin Reporting Independent of Military Oversight, Page B12, April 11, 2003.

Embargoes vs. Deadlines

Largely credited to Victoria Clarke, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs, Bryan Whitman, and other service chiefs of Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps units in the Pentagon, and approved by Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, the embedment process required journalists to agree to certain restrictions or risk termination of their placement. Restrictions included an embargo on time sensitive operations and locations that could possibly compromise troop movements, classified material and a rule prohibiting “photographs or other visual media showing an enemy prisoner of war or detainees’ recognizable face, nametag or other identifying feature,” citing provisions of the Geneva conventions of 1949. “The Geneva convention is a legal document,” said Whitman, “There are different interpretations. But our lawyers felt that it was the basis for a ground rule that established guidelines for photographing epws from a distance, so we had to strike a balance while trying to provide an appropriate level of access.”

The Defense Department was serious about following through on consequences for journalists who did not abide by the rules. Whitman said that only a handful of embedded journalists, including one or two unilaterals, were pulled from their positions. “It was rare,” he said, “and [it was] mainly for rules protecting operational security.” But a compelling close-up image of an Iraqi detainee being strip searched by marines, taken by Cheryl Diaz Meyer, of the Dallas Morning News, ultimately led to the loss of her embedded position with the Marines Second Tank Battalion. The image ran 2 columns by 3 inches in the Dallas Morning News on April 10, and on the same day, it ran as the lead photo on the front page of the New York Times Nation at War section and was seen by an unhappy Pentagon.

Ken Geiger, Director of Photography of the Dallas Morning News said that most of the requests in the Pentagon’s policy on media coverage were reasonable and the arrangement worked out well for The Dallas Morning News, allowing them to cover the war from positions they otherwise might not have been able to cover unilaterally. “We signed the agreement that if we embed, we’ll abide by the rules as set down by the embedment process,” he said in a telephone interview earlier this week. “We had a long debate on whether to show faces. We told our photographers that if there was a question, to shoot it and we would examine them later on a case by case basis.”

The image in question of an Iraqi, who, according to Geiger, was later released, was a haunting and compelling image of the Iraqi opposition, contrasting with the hundreds of photos that were being transmitted by photographers across Iraq, of American soldiers beating a path to Baghdad’s door. The Pentagon responded on April 11 by advising the Washington office of the Dallas Morning News that Diaz Meyer would lose her position with the Marines of the Second Tank Battalion, a position she had reported from since the beginning of the war in Iraq. Geiger says it was the one restriction that was “hard to swallow.”

“We broke the rules,” said Geiger. “In our haste to share images as Baghdad fell, we were wrapped up in the bigger picture and we lost sight of our agreement. We should not have published it. We should have been better gatekeepers, given our agreement with the military.”

Ultimately the Dallas Morning News sent a request to the wire services and the New York Times to kill the photo, and DMN editors pulled Diaz Meyer from her embedded position prior to her being terminated, and reassigned her to Baghdad to pursue other stories independently.

Geiger says he has heard the argument from the larger newspapers about the objectivity issue with embedded journalists, but says the price of having someone working unilaterally on the outside, for the Dallas Morning News, who had four embedded positions, was enormous. “We don’t have the deep pockets like other larger newspapers,” he said. “We had an opportunity to tell the story from one perspective and we used other means to tell the other side of the story. It is a finite way of saying that our photographic staff didn’t tell the whole story, but our newspaper did.”

The Reporter and the "Poncho Queen"

Although Diaz Meyer was not the first female photojournalist to cover the front lines in war, her photographs and dispatches, sent to family, friends and colleagues via email throughout her assignment, offer a poignant account of the marines of the Second Tank Battalion. They add a humorous and uniquely female perspective of what it was like to be surrounded by hundreds of Marines in battle, living in close quarters. In World War II, 127 American women had secured official military accreditation as war correspondents, some of whom had managed to get to the front lines. But there is little evidence of the level of adversity faced by photographers like Diaz Meyer, 1 of 60 female journalists embedded in Iraq, whose nom de plume was either The Reporter or The Poncho Queen, depending on whether she was transmitting pictures, or taking care of personal business.

Vincent Laforet, a staff photographer with the New York Times acknowledged that although the embed process was largely positive, it did not go well at first. Personnel aboard the U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln were initially wary of journalists, subjecting them to unannounced blackouts, resulting in some missed deadlines in the early stages of the war, 24/7 Public Affairs Officer escorts, rules, which were eventually relaxed. “I have been able to tell the story of the 5,500 men and women on this ship with relatively little interference by the Navy,” he said in his photo essay “The Carrier,” published on The Digital Journalist last month. But, he added,

“One thing had become clear in terms of the embedment process, this is NOT a place where one can be expected to release breaking news.”

Transcripts of meetings between Victoria Clarke, Bryan Whitman, Service Chiefs of the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps Units, with media bureau chiefs on January 14 and February 27, 2003, and posted on the DOD website revealed that the blackout restrictions for Navy embeds were conveyed up front to media managers. (http://www.defenselink.mil/news/Feb2003/t02282003_t0227bc.html). (Note this Pentagon link is no longer live).

In a humorous exchange, Rear Admiral Steve Pietropaoli, Navy Chief of Information who was at the Feb. 27th meeting acknowledged that the Navy was going to impose the “arbitrary and capricious reporting windows rule” as military action began and that in all likelihood, there would initially be blackouts in order to maintain an element of tactical surprise. “You guys would like to be able to go live 24/7 and we would like to be able to control your timing,” he said.

Todd Maisel of the Daily News, embedded with the Seabees, expressed frustration as members from his unit left him behind at Camp Fox during their early missions, citing safety reasons. Rule 3G of the Pentagon rules governing embeds states that “commanders will ensure the media are provided every opportunity to observe actual combat operations. The personal safety of correspondents is not a reason to exclude them from combat areas.” But not all embedded journalists saw combat, though the Pentagon’s intentions were to allow them the opportunity if possible. Maisel spent nearly five weeks at Al Jaber Air Base in Kuwait waiting for deployment orders with his unit, and when they came, the Seabees headed to Umm Qasr where Maisel photographed them building roads, removing explosive water mines and building a park for local Iraqi children, in addition to sending email for many of the Seabees in his unit. While the embedment process fell short of his expectations to be part of the advance on Baghdad, Maisel said being assigned to cover the war in Iraq was a highlight of his career.

Vince Laforet sums up his embed experience:

“In the end my challenge has been to try and tell the story of the people on this carrier accurately and objectively, to show the incredible sacrifices these men and women put in every day, while not forgetting that this is all about what happens when those bombs are released. I do find solace in knowing that I am part of a team and that my colleagues at the New York Times are on the ground in Iraq and will be able to complete the circle and present a full report.”

Photojournlist Peter Turnley, who covered the Gulf War in 1991 outside of the pool system, chose not to embed with a military unit during the current war, preferring instead to cover it as a unilateral journalist in search of a broader view. In a telephone interview on May 7, Turnley said he entered Iraq from Kuwait in the first days of the coalition force invasion, and spent a little over three weeks in southern Iraq covering the siege of Basra by the British military, heading north to Baghdad where he witnessed the fall of the city and its aftermath.

“My choice to work unilaterally was a personal one, and I make no judgment about anyone else’s choice to work in any other way. I have the impression that many of my colleagues did extremely important work as embedded photojournalists,” he said, adding “I do think, though, that it is essential that in the coverage of war, that there is a group of journalists and photojournalists that work independently of being attached to a military unit, enabling a greater opportunity to often linger and witness the full effects of war on people in the country involved.”

Turnley, whose photographs offer a different perspective outside the confines of being embedded in a military unit, says there were some difficulties that he encountered as a unilateral. “I have the impression since returning from Iraq, that much of the public is not aware that officially, it was very difficult for unilateral journalists to work in Iraq. The military, both British and U.S. military officials and the Kuwaiti officials did not officially allow journalists carrying unilateral accreditation to cross the border from Kuwait to Iraq freely. It was more or less the official military position of the coalition forces that unilateral journalists did not have a place covering this most recent war in Iraq. I feel strongly that the unilateral coverage of this war and all future wars is essential for the public to have the full picture of what transpires in conflict.”

Given Americans’ concern for human life, and the military’s determination to avoid unnecessary loss of life and collateral damage, it will be interesting to observe whether the Pentagon will incorporate this thinking into their after-action review and lessons learned, and will make provisions – or allowances, for journalists wishing to work independently of the military in the future.

For now, perhaps one of the greatest benefits of the embedding program has been an altered perception of the media by many in the Pentagon. “Although I’ve always viewed the media as hard-working,” said Whitman, “it gave many military members and commanders newfound respect for their dedication and willingness to assume risks and put their lives on the line.”

November 1, 2000

© Susan Markisz, Contributing Editor/The Digital Journalist

Kindly copy and paste the link into a new browser window

http://digitaljournalist.org/issue0305/smarkisz.html

You Don't Win a Pulitzer by Accident

A multimedia interview produced by Susan Markisz

Photojournalism has resurfaced in at the corner of Court Street and University Avenue in Newark, New Jersey.

On the eve of the Millennium, the fledgling photo department of The Star-Ledger found itself in the middle of a renaissance. Fifteen minutes into the New Year, on January 1, 2000, photographer Matt Rainey began digitally transmitting his photos of the New Year’s celebration in Times Square, commencing with an “Auld Lang Sine” to the past, and a nod to the paper’s emergence as a major player in newsgathering and image making in the 21st Century.

Despite the gloomy forecast about the demise of photojournalism, The Star-Ledger has ignored the rumor mill and instead, has concentrated on reinventing its photo department.

In the waning hours of 1999, Rainey had been employed, not as a staff photographer of The Star-Ledger, but as an employee of the independent New Jersey Newsphotos, where he had worked for five years. The sub-contractor had provided coverage for the 406,000 daily circulation paper (605,000 Sunday) for forty years. That relationship was destined for change in October 1999, when James P. Willse, Editor in chief of the Star-Ledger and Pim Van Hemmen, Director of Photography, decided to create an in-house photo department that would become operational as the ball dropped in Times Square on January 1, 2000.

According to Van Hemmen, who was named Assistant Managing Editor for Photography last year, photography was not a high priority under the old arrangement. “Historically, the Star-Ledger did not have a photo department. It was a necessary evil,” he said, referring to the second rate nature of the relationship of photos to the newspaper. Photo requests were electronically transmitted to New Jersey Newsphotos. Once photographers had completed their assignments, film was processed and technicians at New Jersey Newsphotos, located several miles away, transmitted photographs over a T1 line to the paper. There was never any dialogue between photographers and editors. In fact, said Van Hemmen, “picture editors and photographers were discouraged from talking to one another, which was an impediment to doing business. I – and others – felt that we needed more interaction among photographers, reporters, and photo editors, for the paper to get top quality photography.”

Quality photography is exactly what they got, with an immediate return on publisher Donald Newhouse’s investment in the new photo department, and his now in-house staff of 30 photographers. Nineteen days into the new year, photographer Matt Rainey, who had symbolically brought The Star-Ledger into the new millennium with his New Year’s Eve front page picture, embarked on an eight month photographic project, resulting in the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for feature photography, only a year after the photo department’s rebirth.

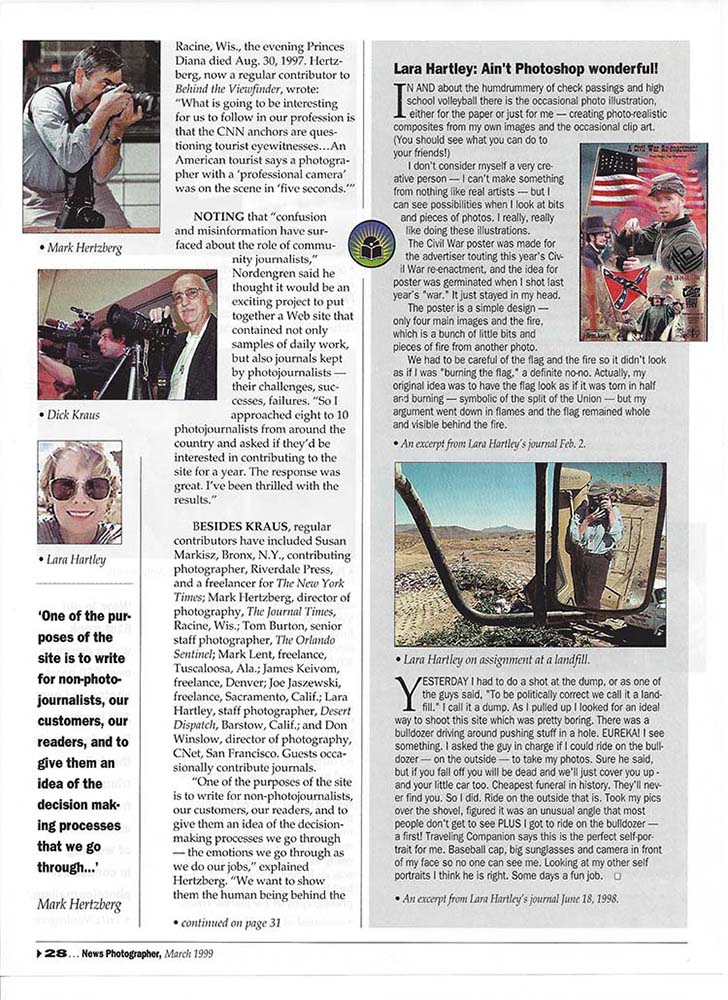

Star-Ledger Photographer Matt Rainey (center) embraces (L-R) Alvaro Llanos and Shawn Simons, after winning the 2000 Pulitzer Prize in Feature Photography for a story about the two Seton Hall students who recovered from a fire in their dorm. Photo by Saed Hindash/The Star-Ledger

Rainey’s work produced a compelling black and white documentary photo essay of the aftermath of the Seton Hall University dormitory fire, which claimed three students’ lives and injured more than sixty others, some critically. The 34-year-old photographer spent eight months with critically injured students Alvaro Llanos, Jr. and Shawn Simons, documenting their painful rehabilitation and recovery in the burn unit of St. Barnabas Medical Center.

The resources that the department devoted to the project went beyond the scope of what Van Hemmen initially thought would be necessary. “I figured maybe he [Rainey] would spend one or two days a week on it, but after working every day for a month, I realized he was going to have to work on it pretty much full time till we published it,” said Van Hemmen. With Rainey pulled off daily assignments, working virtually full time on documentation of Llanos’ and Simons’ recovery, publication did not happen until eight months later.“Eight months was a pretty bold commitment considering we had just started the department, but I wasn’t concerned about it,” adds Van Hemmen. “In order to get great photographs, you have to give people the time to do the job, to maximize the time they have in the field.” Van Hemmen’s philosophy is “to produce the best pictures possible on a given day.” But he also feels that the paper should be producing larger scale projects as well, “with greater scope and depth that give the reader a sense of what life is like for others.”

There is plenty of evidence to suggest that the average person is visually oriented, emphasizes Van Hemmen, referring to the World Wide Web, MTV and television. He nevertheless is surprised by the fact that there are fewer photographs in newspapers these days and insists, “21st Century visual journalism is what people are interested in.”

“We have to be careful about how much newsprint we consume,” adds Van Hemmen, “that is a reality, but it just means we have to pick our opportunities more carefully.”

Van Hemmen is forward thinking about other opportunities. “I want to make sure that we are on the cutting edge using both still and video on the World Wide Web and we should look for more ways to find markets for still photography. Some of it will depend on technology and bandwidth,” he adds. Van Hemmen is also looking into other more traditional outlets like art exhibits, books, and art shows. A first ever calendar will be for sale in the near future.

Maximizing the allocation of resources is a challenge in any business but with diminishing advertising revenues and the cost of newsprint, editorial space is at a premium now more than ever, if one believes what is being said in photo departments throughout the country. Even before managers started complaining about ad revenues, environmental portraits and the celebrity portrait “du jour” had become the default picture worth a thousand words in many publications. Few photographers can argue with the veracity of at least some of management’s claims. But with a shrinking news hole, staff reductions and photographic coverage reduced to an “after the fact” consideration, morale among photojournalists who care about the future of their craft, has been low for years. At a time when photo coverage has been truncated at many papers, Star-Ledger Editor Jim Willse’s vision and commitment to build a new photo department, has raised the bar for photography, and is welcome news to those who have predicted the demise of photojournalism.

“I got to the paper six years ago, and found the eccentricity that the paper did not have its own photographers,” recalls Willse. “I can’t think of another big paper that essentially outsourced its photography.” With the photo staff “physically in another building and spiritually somewhere else,” the arrangement with the subcontractor was not conducive to producing great work. Willse’s plan envisioned producing exceptional work by the photo department, and both he and Van Hemmen were determined to bring in a Pulitzer Prize within three years of the new photography department’s inception.